Drawing and Painting: Perceptual theory as a basis for learning how to draw, by Martin G. Mugar

While Mugar never mentions the construction of cathedrals in Drawing and Painting, his approach got me thinking about what that might mean in one’s own art and teaching.

Humans are tremendously fickle creatures, and sometimes when things go out of style, we have a hard time seeing them for what they are.

In April of 2019, while the world held its breath and Notre Dame burned, I couldn’t help but think of certain ironies concerning the near universal esteem – or even veneration - being expressed for that cathedral at the prospect of its loss. This in contrast with the ubiquitous scorn the structure was viewed with only two-and-a-half centuries before. In fact, the rise, fall, and rise again in the fortunes of its reputation – from the late Medieval period to the Enlightenment and through to the Romantic era - could be seen as a classic case study of the vagaries of stylistic perception over time.

The Gothic style’s plunge into disrepute got me thinking about current trends in our perception of Modernism, whose once powerful cache has seen a significant drop in our lifetime. We tend to forget that Modernism wasn’t a monolithic movement or aesthetic, and neither was the Gothic. Rather, the modern period was a century of varying forms where a whole spate of conflicting definitions of art’s essential nature were proposed. Because of its general ideological fervor, our Postmodern eyes tend to see Modernism in hindsight as a highly controlled set of styles, ideas, and institutions. The paradoxical thing is that this race to delineate and limit the parameters of art came out of a desire for freedom from traditional, academic forms and constraints. The early Modernist’s initial impulse was the ambition to build something new from the ground up, not as groups or a collective society (that happened later,) but as individuals.

Martin Mugar’s book, Drawing and Painting, grows out of much of the same soil early Modernism did, i.e. the desire to build painting anew, one artist at a time, with individual human eyes. This book places the act of visual perception squarely at the center of both drawing and painting. It encourages the student to cultivate their own cognitive awareness in the act of seeing. Its underlying premise is that vision isn’t just an open window for plundering stylistic preferences or narrative material. It’s not merely a tool in the shaping of our aesthetic or conceptual inclinations, but a deeply significant, ongoing, experiential act, never ancillary. The “eye is always in the process of stabilizing the world” according to Mugar, and the very essence of drawing is grounded in “this ordering of perception.”

As I read this book, I was struck by the notion of someone still believing, in very strong and certain terms, that artists can truly innovate through persistent looking, analyzing and feeling. One senses there is still something of the same naive sophistication bouncing around in the author’s head that was present when painters like Monet, Matisse, Braque and Marquet first stepped out into the French countryside to re-discover painting via the observation of nature, or “nature seen through a temperament,” as Zola put it, though I’m guessing Martin might be prone to replace Zola’s use of the subjective term “temperament” with language more firmly grounded in visual function. This is because 150 years later, Mugar’s book is backed up with more cognitive and art historical data, which he mines to make a logical argument for his premise.

Martin’s theory emerges out of decades of experience, from both his studio work and his teaching practice. It is informed by his extensive knowledge of Art History and an intense personal interest in philosophy. Alongside this there are specific investigations into cognitive science as it relates directly to certain visual issues. Most all the details of this knowledge stay in the background however, as Mugar offers up a series of practical exercises. These are laid out as something like arenas for the exploration of vision itself. We are given points of focus, each designed to tap into certain aspects of visual processing. Discoveries are left for the student to unearth through a visual, Socratic question and answer process. Formal issues are dealt with experientially and through looking rather than by describing a particular design concept: Drawing, cutting, collaging, finding negative shapes, using the imagination and redrawing. On the painting side, certain lighting and color parameters are established. There is a strong emphasis on starting out each exercise within its given boundaries, but there is also a feeling that the thoughtful game of chess, once established by those original limitations, could land the student just about anywhere. The destination is not restricted. There are unlimited possibilities in starting from inside those borders.

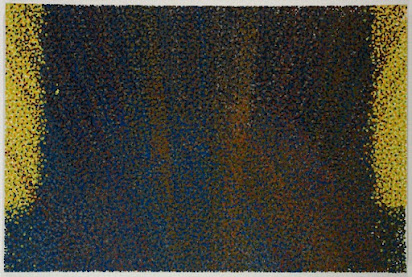

I would be hesitant to strictly call these exercises or assignments, and I doubt they are something to which one could firmly attach a grading rubric of the check-list variety (thankfully.) This doesn’t mean they lack objectivity, as Mugar is a stickler for really making you look at what’s going on in front of you. Caravaggio, Seurat, Cezanne and Braque figure prominently in this book, not for any emphasis on their stylistic flourishings, but because Martin relates certain perceptual functions to what each of these artists did on the picture plane, and how each one saw in new and innovative ways. He orders these exercises according to a different logic of sequence than most teachers I have encountered, starting with those visual processes that happen deeper down in the brain: A nod not only to cognitive science, but to simple intuitive experience as well.

While Martin doesn’t explicitly stray into the depths of philosophy proper in Drawing and Painting, we get hints of how his knowledge in that field enriches this book. One can see his interest in the thought of Heidegger - or perhaps other flavors of phenomenology and existentialism – permeating the mental atmosphere of its pages. Martin’s approach is also philosophical in this way: he does not offer up recipes or a set of instructions. Even with specific projects given, one must attempt to penetrate the meaning of each working situation he sets up through action and reflection. Though simple and straight forward in some ways, all is left open enough to be somewhat opaque and elliptical in terms of end points. Single sentences can be mined and reflected on for manifold implications. This book will utterly elude and exasperate the student who is looking to memorize technically rehearsed answers for surety and peace of mind. It is not a how-to manual.

Drawing and Painting calls us to ask questions, frame inferences, and create something of our own conclusions while being given a partial tour of the territory. The whole map is not handed to us, a priori. Instead, we are initiated into a knowledge of how to navigate the wilderness. What we discover in that wilderness is left up to us.

With its compact, elliptical prose this book is somewhat short, and I found myself wanting more. While he dips into certain aspects of perceptual science – the striate cortex was one that was new for me – there are many others that he leaves alone. I went away feeling like other, unmentioned aspects of vision, like depth of field, the fovea, and center surround, could each have had their own set of exercises tailored for them – along with many others. Or did the author decide that in the case of this book, less really was more? This would leave open the possibility that Mugar treats teachers like he does his students, and those things are left for us to figure out in our own curricula.

In any event, this is an important and timely book. Much of its significance is its tendency to go against the grain of our present-day reasoning. The algorithm, the template, the prefab architectural plan, these are the spirit of our current artistic age. We are offered an array of various templates which give the illusion of freedom. If followed, no thinking or feeling of your own is required. Sharpen your pencil, measure this, measure that, rinse, wash repeat.

Part of the beauty of Gothic cathedrals, and much of the reason we admire them today, is that they were constructed with no architectural plans. Their engineering specs were worked out during the construction process. The builders of Notre Dame defied gravity by experiment, by an intuitive understanding of their materials and the laws of physics. Drawing and Painting is a call to something similar. It is a call to build painting from the ground up, but in this case through an intimate, experiential knowledge of the laws of visual perception. To some that may seem old fashion. To others, it may be the only new way through.

- Miles Hall, December 3, 2021

Martin Mugar currently resides in New Hampshire. His writing appeared on Painter’s Table.

Book is available at: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1475021364