|

| Charles Giuliano |

This document of the 150 year history of the Museum of Fine Arts is mostly cobbled together from interviews by Charles Giuliano of the actors who shaped that history. One of the first is a 1976 interview of a Globe writer who was part of a team that wrote an expose to take down (or so it appeared ) the newly appointed MFA director Merrill Rueppel. It sets the theme of interviews that expose the machinations of behind the scenes struggle between the old guard board and efforts of others to bring new blood into the Museum. Charles has been connected to the Museum soon after graduating from Brandeis when he was employed in the Egyptian department. He stayed close to the museum via these interviews in his role of journalist for multiple Boston newspapers. He clearly has garnered the respect of his interviewees. Considering that he rarely lobs softball questions one might think that it would have been wiser for them to avoid him, but almost fifty years later he brings the reader, without skipping a director, up to the present with an interview of the current director Matthew Teitelbaum. Maybe the numerous directors all felt that they have to post the “Charlie card” on their resume in order to be truly enthroned as director of the MFA.

Getting a conceptual handle on these interviews and the scrutiny they provide in the context of the history that came before, is a bit of a struggle. I fell back for help on the template of a recent book by art critic Jed Perl: Authenticity and Freedom. Authenticity can be seen as meaning tradition and often in Perl’s hand as something numinous and quasi-religious. A case in point is his use of an anecdote about the musical career of Aretha Franklin. She had her start as a singer in her father’s church choir. She was imbued in the gospel tradition of singing that had a long history in black American culture. When she made the break (freedom) into popular music that tradition was always there to shape her new music. The music had roots. The origin of the MFA as a recipient of invaluable Japanese art at its beginning was similar and had a purity that nothing in the later history of the MFA could match. Its collection of Japanese art was given by bluebloods Morse, Bigelow and Fenellosa who lived in Japan as practicing Buddhists and in their collecting of the Japanese artifacts had eventually received the imprimatur and permission of Japanese collectors and scholars such as Okakura Kakuzo, who in turn became the first curator of the Boston collection. Moreover, Okakura was a world-renowned scholar of Zen Buddhism whose “Book of Tea” is purported to have influenced Martin Heidegger’s understanding of Japanese thought when Okakura studied under him in Germany. The Japanese who were initially shocked by the export of national treasures such as the “Burning of the Sanjo Palace” put a stop to any further expatriation. They eventually accepted it as a way of sharing the Japanese cultural heritage with the world. However, this is to be contrasted with the unseemly attempt to transfer a Raphael from Italy to Boston by Perry Rathbone toward the end of his tenure that necessitated a whole book by his daughter to rehabilitate his reputation. Jan Fontein, director and curator of the Asian collection said that these exchanges with the Japanese were a generation ahead of the ”repatriation movement” .

Money and lack thereof becomes another leitmotif of the book. Bigelow was well off. The Japanese collection was well endowed. Moreover, its cultural value was never questioned. These were cultural treasures by deceased artists. A hilarious anecdote that sheds light on the topic of money in one interview relates the reaction of a French curator of Textiles at the MFA, who lashed out at Alan Shestak in a meeting of curators that he was tired of hearing about money, and that in Lyon, where he worked in the museum, to talk about money was beneath them. He refused to shut up about his opinions and eventually was fired. He refused to leave his office and had to be chased out by the police in keystone cop style. Of course, in France everything is paid for through taxes up front and one never knows the real cost of things. The Metropolitan in New York receives millions from the state of New York. Boston nothing. The National Gallery gets all its money from the government. Expenses always seem to exceed income even during the halcyon days of Malcolm Rogers who somehow increased the endowment but increased the debt at the same time.

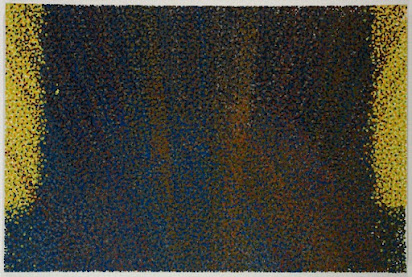

Later in the book a recurring theme is who among contemporary artists should be collected. Ananda Coomaraswamy, the curator of the collection of Indian art (1933-1947) felt that no living artist should be collected. Problem solved. But the MFA was expected to collect Boston artists, first the Brahmin Boston Impressionists and then the Jewish Boston Expressionists (Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe). A thorough collecting of the latter was obviated due to rampant anti-Semitism. Every curator had their faves. One director liked Hyman Bloom up to a point and another only looked at Color Field but could not tolerate Hans Hoffman. Merrill Reuppel turned down the purchase of Pollock’s “Lavender Mist” which at the time was reasonably priced and was soon acquired by the National Gallery. The turning down of this masterpiece is another recurring theme of lost opportunities, along with the dearth of “modern classics” by Picasso and other cubists. Somehow the MFA never heard of the Armory Show. They would eventually get a Picasso but it was not one of his best. When I taught at UNC-Greensboro they had in their collection one of De Kooning’s women. The story behind its purchase is that it was bought for $5000 dollars and the director was fired for spending too much on it. Unfortunately, such a serendipitous mistake was not made at the MFA.

|

| What could have been:"Lavender Mist" |

As a born and bred Bostonian, Charles does a great job of following the vagaries of the city’s economy to which the success of a director and the MFA seemed inextricably tied. The period of the establishment of the Ancient Egyptian, Classical Greek and Roman, Japanese and Indian collections corresponded to the building of Back Bay. The sluggish economy of the 1970s when townhouses in the Back Bay were going for $70,000 weighed heavily on the Museum’s ability to raise money.

To stick with the conceptual structure of Authority and Freedom that Perl provides: i.e. freedom would be the letting go of the authority of the early collections of Asian art works with which early curators established their authority at the inception of the MFA.. The freedom might be more related to the necessity of responding to the multiplicity of art forms and styles that in fact the museum has a hard time keeping on top of and on dealing with the issues of racial equity that must be addressed if the Museum is to garner the respect of and truly represent the community. Racial tension has always been a reality in the Boston community that the Museum has mostly tried to ignore and struggled to address. But that is far from the days when housing and displaying the artifacts of ancient cultures were the only worry. The business side that so upset the French curator did not reduce everything unnecessarily to the big buck but, according to Barry Gaither, adjunct curator of African American Art, the arrival of Seybolt, a so-called uncouth Midwesterner from the business world of Underwood Devilled Ham to the board of trustees, was appalling to some but to him a breath of fresh air. Gaither a black saw himself as another outsider like Seybolt. And when someone mentioned that Rathbone was not a Bostonian, Gaither answered that he was trained at The Fogg. Seybolt a protégé of former MIT president Howard Johnson had strong Washington connections that would become crucial in getting financial contributions from DC to support travelling shows.

The mostly Brahmin board probably lived in the glow of the MFA’s early days when they were able to keep the museum self-sustaining but not expanding. Keeping the museum up to date, after the market crashed in the late ‘60s, probably required the intervention of the Seybolt/Rueppel regime. The expansion of the US government in the days of the Great Society required that the Museum establish Washington connections belying the vision of the centrality of Boston as the Athens of America. Already left economically behind by New York City it could not blithely ignore Washington DC as a source of money.

How will it deal with the virtual museum? The NTP? Just as the advent of Zoom in the age of Covid unexpectedly opened up the possibility of working from home so the virtual museum of the metaverse might do the same to the museum goer. How does the Museum continue to take in revenues in a wide open world of art without walls? And how does racial equity differ from racial equality in its impact on the functioning of the museum within the community? The goal of the MFA should be to exert its freedom by staying ahead of the game and not play "catchup".

What these interviews succeed in doing is conveying the increasing multidimensionality of the Museum over the years from simple roles of storing, curating and exhibiting art, to the never ending need to raise money and the imperative of community outreach. Although at times the directors seem hapless and self-absorbed, they all in their own way add to the success and survivability of the MFA. Charles Giuliano who is one of the few Boston Critics to observe the Boston Art Scene holistically has included in his quiver of accomplishments a global understanding of the MFA.

Link to buying the book on amazon